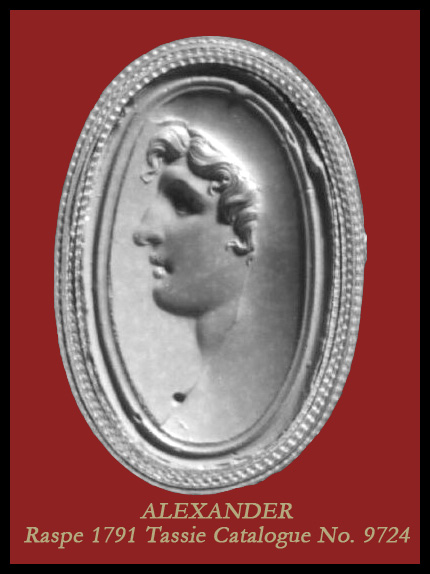

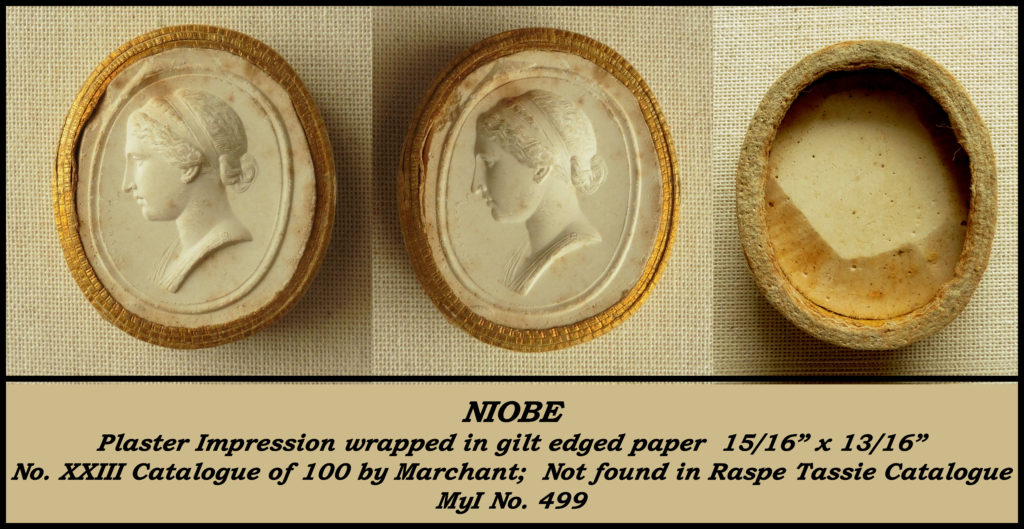

In 1792, not too long after his 16 year stint in Rome, Nathaniel Marchant published a catalogue listing 100 impressions of gems he had engraved, which together with a set of the impressions, was made available by subscription. The catalogue listing was by subject or name and short text description having no images included as reference.

Complete original sets of impressions found today (I could only locate 6) are not always organized to reflect the order followed in the listing. The most informative literature about Marchant and his works, “Nathaniel Marchant, Gem-engraver 1739-1816”, by Gertrud Seidmann, Walpole Society, vol. LIII, 1987, pp. 1-105, while having images of each impression, does not make it easy to relate each catalogue item to its image because the subjects are listed alphabetically interspersed with additional, other, items by the artist.

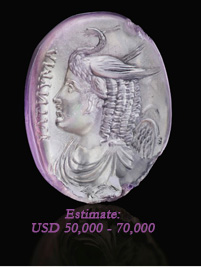

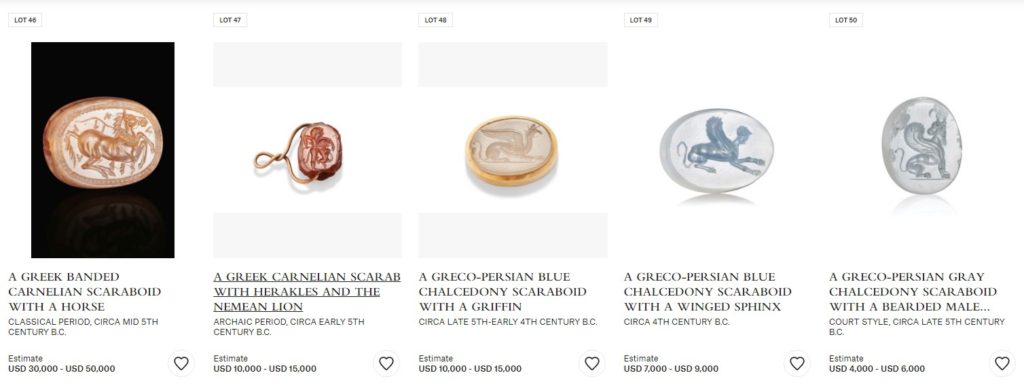

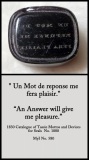

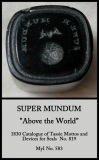

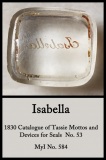

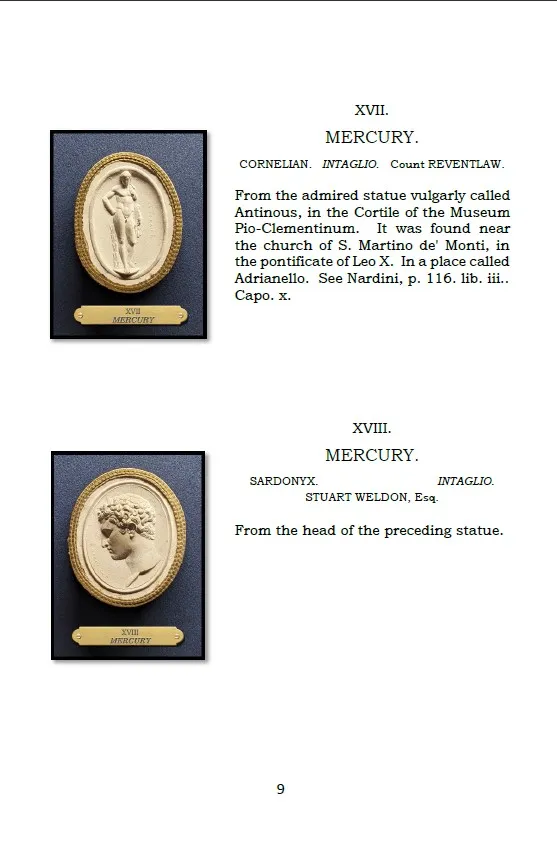

In order to present each individual item in the catalogue together with its image, a new, reproduction catalogue has been prepared. Two sample pages are shown below.

This reproduction catalogue can be downloaded as a .pdf file from THIS LINK

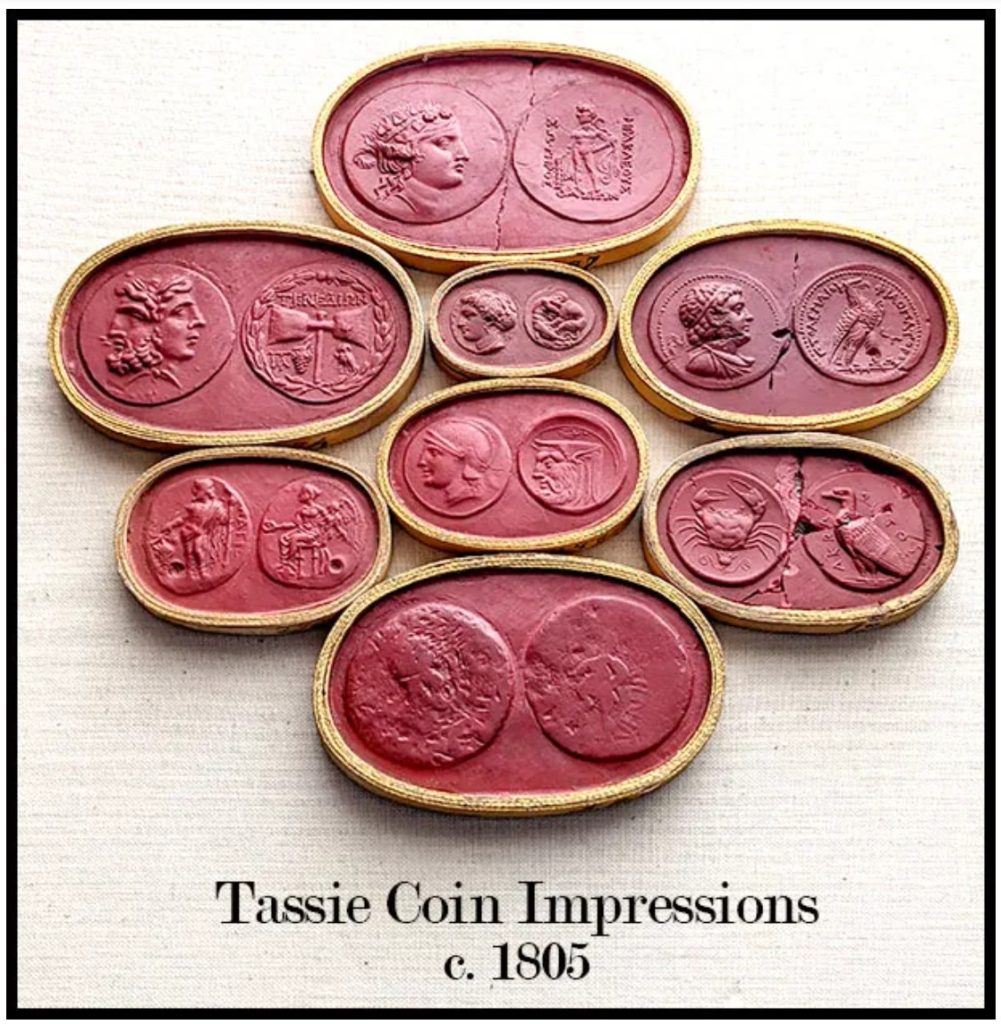

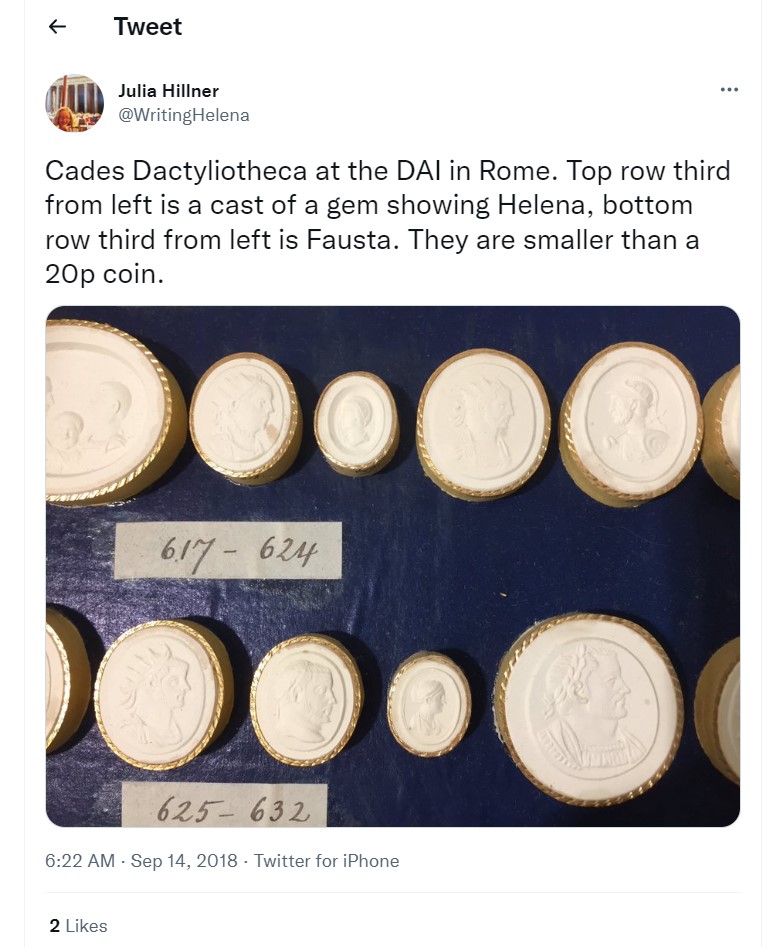

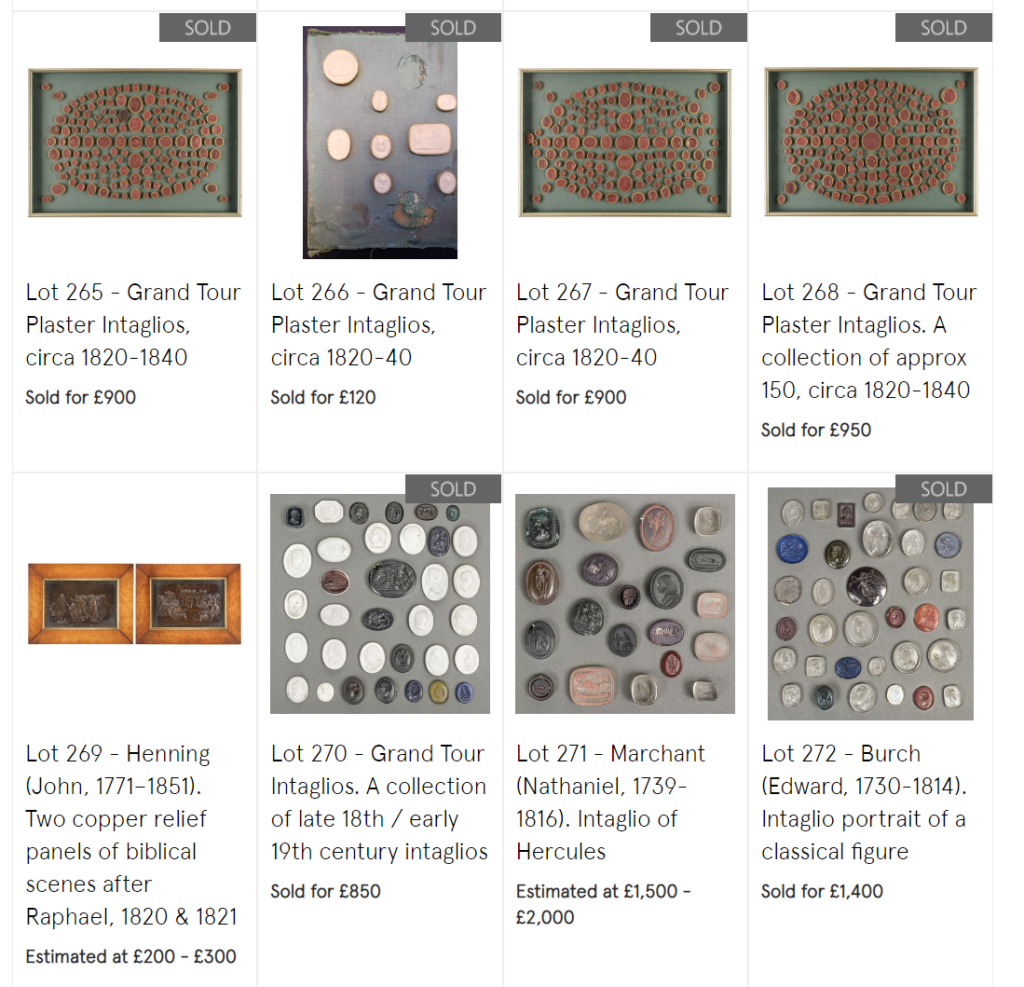

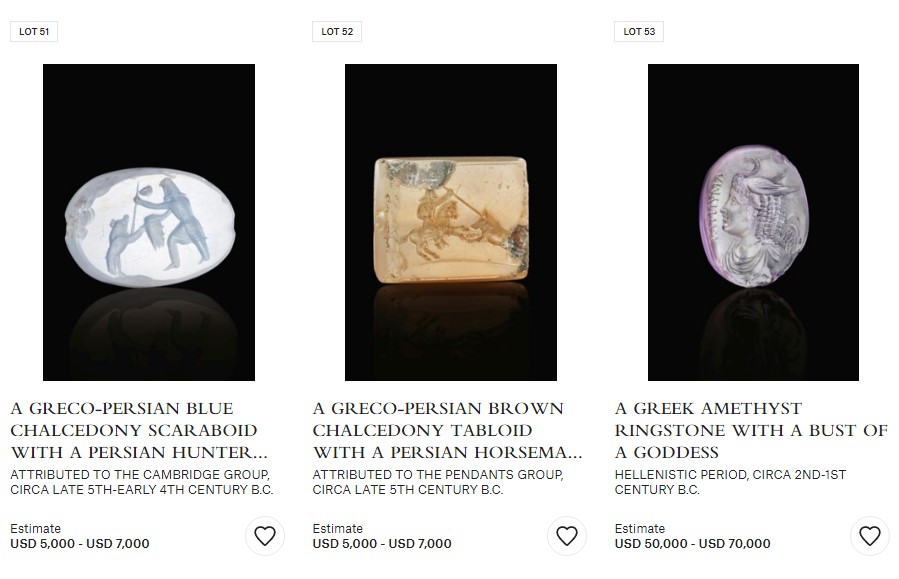

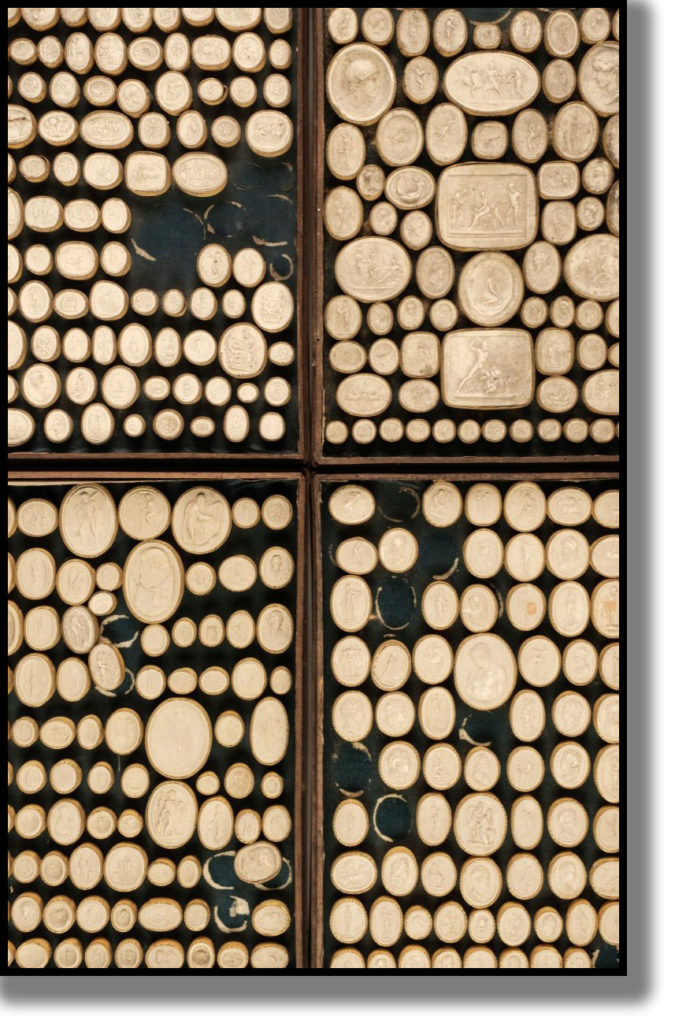

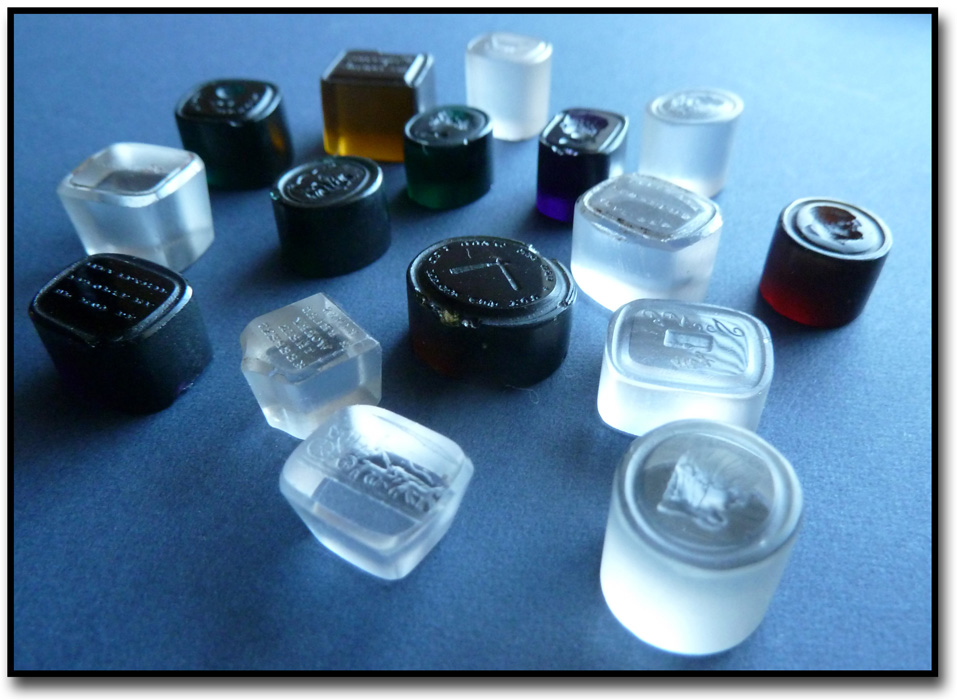

The impressions of engraved gems (and their copies) by Marchant are some of the most recognizable of all of the impressions from the Georgian and Victorian ages. The hundred included in the catalogue are almost exclusively of classical figures and allegories. It’s rare today to find a set of Grand Tour era casts that do not include several by or based on engravings of Marchant.

It is hoped that this reproduction catalogue will be useful to all who are interested in Marchant and his works and that it may even generate some new interest in them.

Enjoy.